“What are you afraid of losing,

when nothing in this world truly belongs to you?”

— Marcus Aurelius

It’s a question that doesn’t demand an immediate answer. Instead, it lingers. It follows you into quiet moments, into moments of anxiety, into the subtle tension you feel when you try to hold life still.

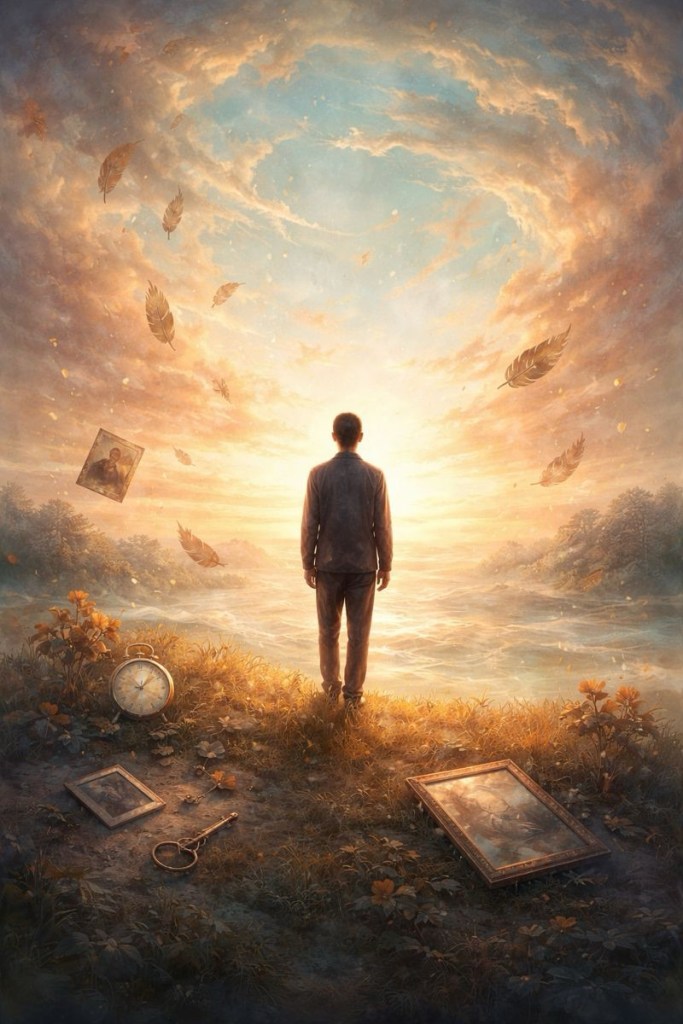

Much of our suffering begins with the fear of loss. We fear losing people, status, comfort, identity, time. We cling tightly, believing that if we hold on hard enough, we can protect what matters. But Stoic philosophy invites a different perspective: what if nothing was ever truly ours to begin with?

Marcus Aurelius didn’t mean this in a cold or dismissive way. He wasn’t suggesting we stop caring. He was reminding us of something deeply human — that life is temporary, fluid, and beyond our control. Everything we experience is borrowed: relationships, health, success, even the present moment itself.

The problem isn’t love or ambition. The problem is attachment — the belief that we own outcomes, that things shouldstay the same, that change is a personal betrayal. When we attach ourselves to permanence in an impermanent world, anxiety becomes inevitable. We start living defensively, guarding what we have instead of fully experiencing it.

Stoicism teaches that peace doesn’t come from controlling life, but from aligning ourselves with reality. When we accept that change is unavoidable, we stop wasting energy resisting it. We begin to appreciate instead of possess. Gratitude replaces fear.

This doesn’t mean becoming distant or emotionally numb. In fact, it often has the opposite effect. When you accept that nothing lasts forever, moments become more precious. Love becomes more intentional. Presence deepens. You stop postponing joy for some imagined future where everything feels “secure.”

A Stoic approach asks us to love without clinging, to care without demanding guarantees. To say, I am grateful for this while it is here, rather than I need this to stay.

A simple practice is to observe what you’re afraid of losing and gently question it. Ask yourself:

- Is this within my control?

- Am I appreciating this moment, or just protecting it?

- What would change if I allowed this to be temporary?

You may find that what you’re truly afraid of losing isn’t the thing itself, but the identity or safety you’ve built around it. Letting go of that illusion can feel unsettling — but it also creates space. Space for calm. Space for freedom.

When nothing is owned, everything becomes a gift. And gifts are meant to be received fully, not guarded anxiously.

So the question remains — not as a challenge, but as an invitation:

What are you afraid of losing, when nothing in this world truly belongs to you?