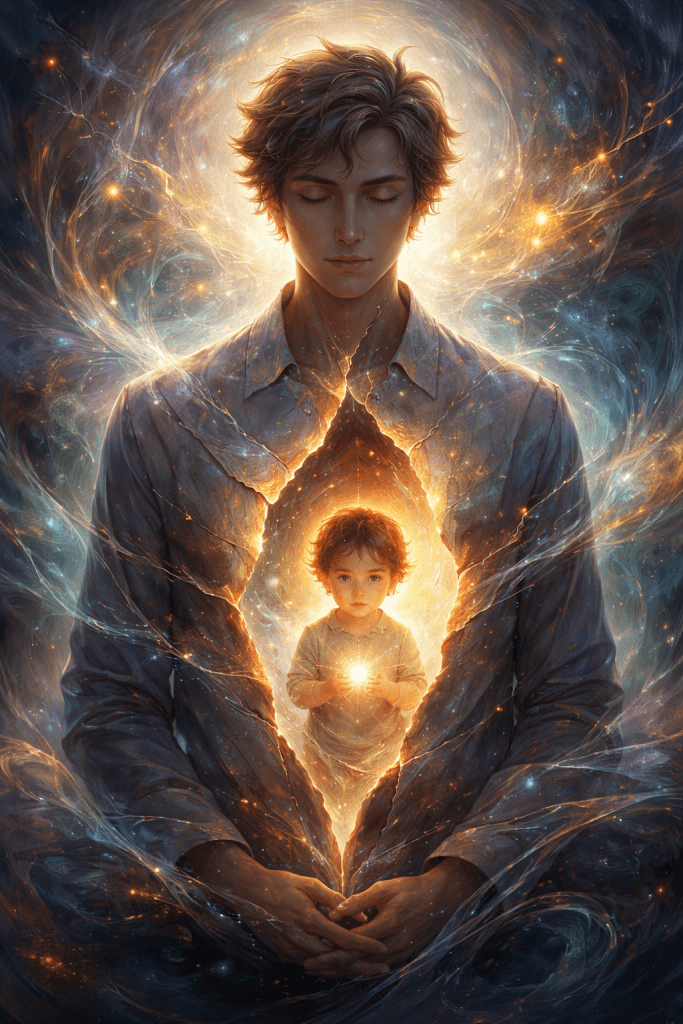

From the outside, some people appear composed—measured words, thoughtful pauses, a quiet confidence that feels earned. They speak like philosophers, as if they’ve wrestled with life and emerged with wisdom neatly folded into sentences. But inside, they are often something else entirely: a child, wide-eyed and wandering, holding onto a sweet delusion just to make sense of the world.

Fyodor Dostoevsky captured this contradiction with unsettling precision. The maturity others see is often a skill, not a state of being. It’s learned through necessity—through disappointment, loss, and the slow realization that raw honesty isn’t always safe to show.

We learn early how to sound put together. We refine our language, temper our reactions, and polish our thoughts until they resemble stability. Society rewards this. Calm is mistaken for strength. Intelligence is measured by how well we can explain pain without showing it. Over time, the mask becomes convincing—not just to others, but to ourselves.

Yet beneath that mask lives the child.

The child is not foolish or naïve. The child is the part of us that still feels deeply, that hopes without guarantees, that imagines meaning where none is promised. This is the part that believes life should be more than survival, that love should be gentle, that understanding should come naturally. When reality proves harsher, the child doesn’t disappear—it retreats inward.

What Dostoevsky calls “sweet delusion” is not a flaw; it’s a refuge. Imagination becomes a place to rest when the world grows too rigid. Fantasy softens the sharp edges of existence. It allows us to keep moving forward without becoming brittle. Without it, many of us would harden beyond recognition.

But there is a quiet tension here. The philosopher learns to analyze feelings. The child simply feels them. The philosopher explains suffering; the child asks why it hurts. And often, we side with the philosopher because it feels safer to understand pain than to experience it fully.

We’re taught that emotional vulnerability is immaturity. That sensitivity must be outgrown. But what if that’s backward? What if true depth requires access to both—the clarity of thought and the innocence of feeling?

The danger isn’t in having an inner child. The danger is in silencing them completely. When we deny that part of ourselves, wisdom becomes hollow. Insight loses warmth. We may sound intelligent, but we feel disconnected—estranged from the very emotions that give life meaning.

Real maturity isn’t emotional suppression. It’s emotional integration.

To be whole is to allow the child to exist alongside the philosopher—to let curiosity live with reason, imagination with realism, vulnerability with strength. The child doesn’t need to lead, but they do need to be heard.

Because the truth is this: the people who understand life most deeply are often those who never fully outgrew wonder. They learned how to survive the world without letting it erase the part of them that still believes life can be tender.

And that isn’t delusion.

That’s humanity.